Kagawa Prefecture: Entering Nirvana

Prologue

Kagawa symbolises the realm of Nirvana, but two days into this fourth and final stage of our Shikoku Pilgrimage, the winds brought grave news of our brother-in-law’s health. As the cherry blossoms faded, we paused our pilgrimage and returned home.

Three weeks later, our ‘loud and vibrant’ brother-in-law Ray died, leaving a sea of sorrow in his wake. We stayed close to home through the Australian winter and into spring. Then as Melbourne’s days were lengthening, we returned to Japan in early November. The weather was cooling and the nights descended early.

We took up where we left off, at Dōryūji (Temple 77), hoping to regain the spirit of the pilgrimage and, if not reach nirvana, at least complete our walking journey around Shikoku.

Day 37 (cont.): 31 km/Temple 66

The April sun shines brightly as we cross from Ehime into Kagawa prefecture. Unpenji (Temple 66) is the first temple in Kagawa prefecture and the highest point of the Shikoku Pilgrimage. It’s a nansho, a difficult place to reach. The path to the temple is a henro korogashi; a steep, slippery section where pilgrims risk falling. It’s a relentless climb that requires us to be vigilant to avoid losing our footing on loose stones or tripping over tree roots.

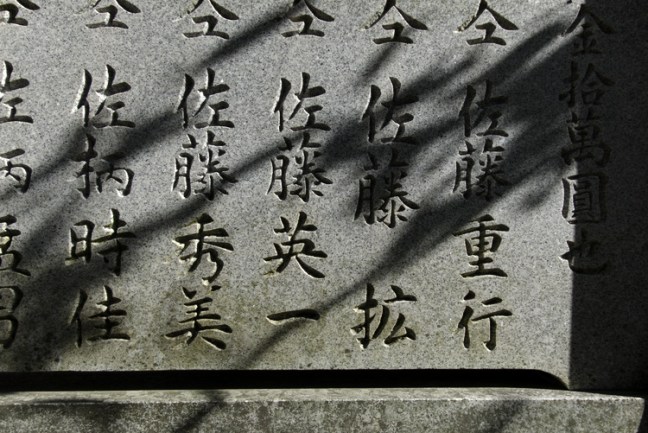

Address-wise, Unpenji is in Tokushima Prefecture but as a sacred site, it’s the first temple in Kagawa, Japan’s smallest prefecture. Surrounded by thousand-year-old cedars and shrouded in clouds, the temple is guarded by 500 life-size statues of arhats (‘saints’ who have attained nirvana). Each statue has a unique character; some are long-suffering, some ferocious, and some joyful. There are also Jizos and a giant sculpture of an aubergine where wishes can come true.

This mysterious, animated stone world entrances us and we’re reluctant to leave Unpenji. By the time we drag ourselves away, we don’t have enough daylight left to reach our accommodation on foot. Instead, we ride the cable car down from the temple. It’s a thrill to hover mid-air and look out onto sheer rock walls, wild forested mountains and deep, impenetrable gorges.

We’re staying in a run-down train sleeper carriage on a hill overlooking the Inland Sea. It’s a peaceful place and we enjoy a cold beer from a vending machine as we watch the sun set over the hazy white sea; its islands floating on the clouds and not a ship in sight.

Day 38: 28 km/Temples 67-70

A warm Saturday morning. We’re now 1,000 kilometres into our Shikoku Pilgrimage. The mountains taper off as we near the sea. The wheat is ripening; the onions and daikon are ready for harvesting.

Kōbō Daishi founded Daikōji (Temple 67) in 822. It contains the oldest statue of him on Shikoku. However, like many Buddha statues with great power, it’s hidden from view.

We walk through Kan’onji City where old people work the land, even as new housing estates encroach on their fields. On the other side of the city is Kotohiki Park where Jinnein (Temple 68) and Kannonji (Temple 69) are located side by side, the only two of the 88 sacred temples to be positioned like this. There’s also a Shinto shrine that was once part of the Shikoku Pilgrimage. From a hill nearby, we look down on a huge, 17th-century-style coin made of sand. The local people reputedly created it overnight as a welcome present to their feudal lord. Viewing it ensures good health, long life and freedom from financial worry.

Motoyamaji (Temple 70) has a five-storied pagoda and is the only temple with a principal image of Bato Kannon Bosatsu. His head is that of a horse and a horse statue stands near the Hondo where the image is enshrined.

For centuries, Japanese farmers used the blooming of Sakura as a sign that it was time to sow their rice crops. They held elaborate feasts under the trees, offering food to the gods to pray for a good harvest. Near Motoyamaji, we see families and groups of young people continuing the tradition of Hanami, picnicking under the Sakura trees and celebrating the transient beauty of cherry blossoms.

We spend the evening planning the last section of our pilgrimage. The host of our guesthouse kindly assists us in booking accommodation to fill the gaps between here and the end of our pilgrimage. An hour later, we receive news of brother-in-law Ray’s rapidly declining health. It’s a restless night for both of us.

Day 39: 20 km/Temples 71-77

We wake knowing it’s time to pause our Shikoku Pilgrimage and return home. We give ourselves one last day to walk as far as Dōryūji’ (Temple 77), leaving 11 temples for a future journey. As we rebook airfares, our host picks up the phone and undoes the bookings he made for us last night. We are the last to leave the guest house.

It’s not a long day in terms of kilometres but temple visits take time and melancholy slows our pace. As we walk through forests and a string of villages, we come upon mysterious caves, a shabby enclave of abandoned resorts and men hitting golf balls into a stagnant reservoir.

Mt. Iyadani, the site of Iyadaniji (Temple 71), is one of Japan’s most sacred places. Tucked into the mountain rock and surrounded by trees is the cave where Kōbō Daishi studied before travelling to China in 807. We pay our respects at the entrance. There’s a legend that you should not look back when you leave the temple. If you do, you’ll return with the dead on your back. We suppress any desire to cast a backward glance as we navigate the 540 steps from the Hondo to the exit.

We walk back down to the plains to reach Mandaraji (Temple 72), the oldest temple on the Shikoku Pilgrimage. It features a Never Ageing Pine Tree with a sacred image of Kōbō Daishi carved on the trunk; an image we reflect upon to sharpen our clarity of purpose.

En route to the next temple, we walk beneath a sweet-scented froth of cherry blossoms, the ground confetti-pink with fallen petals. Stone statues, haiku monuments and a profusion of flowers line the approach to Shusshakaji (Temple 73). As a boy of seven, Kōbō Daishi tested his faith by leaping off a precipice on nearby Mt. Gahaishi. Mid-fall, a heavenly maiden caught him. The site of the leap is a steep climb above Shusshakaji that offers expansive views out across the Sanuki Plains.

The area around Kōyamaji (Temple 74) was where Kōbō Daishi played as a child. When he was middle-aged, he returned, looking for a site to build a temple. One day an old man appeared from a cave and said, ‘If you build a temple here, I will protect it forever.’ We focus on being truly present as we carry out our temple rituals and write a special wish for Ray on the name slips we leave at the Hondo and Daishido. Ray isn’t religious, but we know he would appreciate us asking the deities to keep him in their thoughts.

Zentsuji (Temple 75) is the birthplace of Kōbō Daishi. In 1934, on the 1,100th anniversary of his death, worshippers erected a statue of him in the temple precinct. Around the figure of Kōbō Daishi are 88 statues representing the Shikoku Pilgrimage temples; if you walk around them, you symbolically complete the 88 Temple Pilgrimage.

At Konzōji (Temple 76), there’s a ceremony in progress. We watch from a discreet distance as a family introduces their baby to the Buddha and their ancestors, thanking them for a safe birth and asking them to guide the child as it grows. A gardener shaping the cherry trees to ensure perfection next flowering season pauses and explains what he is doing. As we leave, he blows a conch shell trumpet. It echoes across the temple precinct, reminding us to follow the right path, the path of compassion.

It’s a warm, lazy Sunday as we walk through the outskirts of Marugame city towards the Seto Inland Sea. The roads are quiet so we take the most direct route, detouring only to find a Konbini (convenience store) where we rest and replenish.

At the time of Dōryūji’s (Temple 77) founding, this was a vast mulberry orchard and silk production area. According to legend, Wake Doryu, a local lord, saw a large mulberry tree emitting a mysterious light. He was suspicious and shot an arrow at the tree. A woman screamed and he found her nursemaid lying dead nearby. Grieving, he carved a statue of the Medicine Buddha from a mulberry tree and enshrined it in a hut.

The day draws in on itself. We complete the last of our temple visits, promising each other that we’ll return and finish this pilgrimage one day. It’s a muted afternoon; the landscape opening out, our hearts stranded between worlds. As the light fades, we follow a deserted road to a rail station, say goodbye to the Shikoku Pilgrimage and turn our thoughts towards home.

Later, we learn that we walked an ancient Seven-Temple Pilgrimage of Grief today. The spirits of the dead and those who mourn them walk this path of sorrow together on a certain day in spring and another in autumn. It was a prescient path to have taken.

Day 40: 3.5 km/Temple 77

We paused our 88 Temple pilgrimage in the Japanese Spring. Now, seven months later, it’s Autumn and we’re back on Shikoku to pick up where we left off, at Dōryūji (Temple 77). We want to complete what we started in honour of Ray, who said in his final days that while we need not have cut our journey short, he appreciated us doing so.

Two elderly monks restamp our temple visiting books. Leafing through the pages, they trace our journey by studying the calligraphy and stamps. They present us with an osettai (gift) of biscuits and lollies; a small shop nearby provides us with a cup of tea. We feel welcomed back to the pilgrimage.

The paddy fields are green with the last flush of this season’s rice crop. From the temple, we walk back to the same business hotel in Marugame where we stayed last time. It’s a relaxing 3.5-kilometre stroll on a sunny afternoon given over to re-finding our walking rhythm. Later, the sky blazes bright with colour as the sun sets; red sky at night, pilgrim’s delight. The hotel foyer is crowded with suited salarymen. They dine on free noodles and drink cold beer from the vending machine. In our white henro vests we resume our identity as pilgrims and look forward to stepping out on the trail tomorrow.

Day 41: 27 km/Temples 78-82

On this crisp sunny morning, our route takes us across the Doki River and past a historical townscape of well-preserved traditional buildings.

When we arrive at Gōshōji (Temple 78), a novice monk is deep in contemplation, raking gravel. He pays no heed to the stunning view of the Seto Inland Sea shimmering in the near distance.

We’ve lost the flow of temple rituals but our guidebook serves as an aide memoire: bow, ring the temple bell to announce our presence, purify ourselves, light one candle and three incense sticks, and bow again.

Gōshōji is a sacred place of worship for both the Jishu and Shingon sects. It’s also where the Shinto-Buddhist syncretism that shaped Japanese Buddhist culture flourished and is still alive. Three monkeys surround a blue-faced deity in the main hall. Behind it are a series of vermilion torii gates marking the entrance to a Shinto shrine. Near the main hall, we brave the stairway that leads to an underground town of phantoms, populated by 10,000 mini Kannon figures.

On our way out of the temple, we meet Neil, a Scottish/Belgian pilgrim in the last days of his long walking journey. He wonders aloud how he will feel at the end of it. Will it be an anti-climax or bitter-sweet? Will he feel euphoric?

In the next town, we stop for coffee and cake at a quaint cafe. Not long after we sit down, a homeless man wearing torn, dirty clothes walks in and orders a coffee. The owner treats him with the same respect as other customers. She gives him a hand wipe, a glass of water, and a biscuit with his coffee. He drinks without sitting and then comes to our table and asks us questions in English (where are we from, what are we doing in Japan, etc.). He offers snippets about himself (he’s from Kobe and is 71 years old) but we learn little of his story before he turns and leaves. Not long afterwards, a woman on her way out of the cafe gives us an osettai of a 1,000 yen note (AUD$10). We’re taken aback but know to accept it graciously and make an offering of it later.

We pass a nondescript factory building transformed into a mosque by a film-set-like plywood facade. (There are around 200,000 Muslims in Japan. In the main, they are foreign-born migrants from other parts of Asia.) In Nishino Sho Town, next to the Sacred Spring of Yasoba, we come upon a wooden hall with an enshrined fibreglass giraffe kneeling in prayer to the Jizo. A second giraffe is lazing by a doorway and yet another is lounging on the verandah. The sculptor, Tomio Okayama, created the works. He exhibited them in the Jizo Hall to cheer up residents when the annual ceremony to honour ancestral spirits was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The giraffes appear to have found a home here.

Tennōji (Temple 79) looks more like a Shinto shrine than a Buddhist temple with its vermilion torii gate towering over the temple precinct. The principal image of Juichimen Kannon Bosatsu enshrined here relates to two teachings intended to save humankind; 1) the Diamond World which manifests as absolute wisdom and 2) the Womb World representing great compassion.

At the temple entrance, we run into Neil again. He’s talking to an American couple he met on the first day of his pilgrimage. The three henros have been walking together on and off since then. Now their paths will diverge. Farewelling people you’ve fallen in with on a long walk is a wrench, so we leave them to say their goodbyes.

It’s been warmer than normal and autumn is late coming. In the lowland areas of Shikoku, the leaves of the ginkgo trees are beginning to take on a golden hue but the maples are still green, the rumoured spectacle of their brilliant reds and oranges a fiction.

Emperor Shomu built Kokubunji (Temple 80) in 741 to pray for the peace and safety of the nation. It’s home to the largest Kannon statue on Shikoku, a secret Buddhist sculpture shown every 60 years; the next public viewing is scheduled for 2040.

Distracted by the breathtaking views of Shikoku’s distinctive, acute-angled mountains, we somehow stray into a military zone. We realise our error when we come to a high, razor-wire-topped fence with a ‘Trespassers Prosecuted’ sign. We have a moment of panic but by a stroke of luck, discover an opening just wide enough to squeeze through. Relieved, we rejoin the henro trail. Ahead is a steep climb up to Shiromineji (Temple 81), located on the furthest west of five sacred peaks. We pause at a viewing platform to catch our breath and take in the sweeping seascape. A group of picnicking men invite us to join them but we’re hard-pressed for time and decline their kind offer. Not wanting us to leave empty-handed, they ply us with cans of coffee and tiramisu to eat later.

Monkeys chatter high up in the trees, and closer to the temple, we hear the devotional chanting of monks. Legend has it that a Shinto folk deity led Chisho Daishi (a relative of Kōbō Daishi) to the summit of Mt Shiromine to receive the oracle of the god of the mountain. He carved a thousand-handed Kannon statue from a fragrant tree shimmering in the Seto Inland Sea and it became the temple’s principal deity.

The light is fading as we scramble to reach Negoroji (Temple 82) before 5 pm. Despite pushing ourselves hard for the last few kilometres, we arrive ten minutes after closing time. The temple office is in darkness. A benevolent monk wandering the temple grounds guesses our plight, unlocks the office and stamps our books for us. One mission accomplished, we turn our attention to the next challenge; a two-hour, post-sunset walk. It requires us to navigate a steep, rough track through the forest with only a phone torch to guide us. Fallen trees, washed-out bridges and the lack of waymarkers make the going tougher.

After an epic 10-hour walking day we’re spent when we arrive at our guest house. The host sees that we don’t have another step in us and offers to drive us to an Izakaya. Left to our own devices, we wouldn’t have bothered but it’s just what we need: a delicious meal, a cold beer, and a lift back to our accommodation.

Day 42: 23 km/Temples 83 & 84

Sea mist hangs in the damp, early morning air. We follow the river upstream. Silver grass lines the banks and migratory birds gather in a shallow waterhole. An old woman is out in the fields, picking flowers. Grapefruits the size of melons grow in the citrus orchards. Persimmons hang heavy on bent branches. These trees have a deep connection to life and death in Japanese folklore and families often hang a string of dried persimmons in their homes on New Year’s Eve to bring good luck and a long life.

On the left side of the main hall of Ichinomiyaji (Temple 83) is a small shrine dedicated to Yakushi Nyorai. Hell’s Cauldron is its name. There’s a legend that the border between worlds will open if you put your head in the opening. But if you do bad things, you will lose your head. Tempting fate, we place our heads in the cauldron. While nothing mystical occurs, we’re relieved not to come to any harm.

Another osettai: a handmade drawstring bag from a woman working at the temple shop. The clouds build and then dissipate. At noon, schmaltzy Western music is broadcast over the town’s PA system, reminding people to be alert to the risk of earthquakes and tsunamis.

We detour from the trail to visit Ritsurin Garden, a large, historic garden in Takamatsu. Completed in 1745 as a private strolling garden for the local feudal lord, it opened to the public in 1875. Considered one of Japan’s finest gardens, we delight in the soothing beauty of its green hills, ponds, ancient pine trees, and teahouses.

On the climb to Yashimaji (Temple 84), signs warn of the danger of wild boar and hornets. We put our faith in the Jizo statues that line the steep mountain path and are known to protect travellers. We pass a Japanese henro walking counter-clockwise (an undertaking that accrues more merit than walking clockwise); apart from him, we see no other henros on the trail.

In 815, Kōbō Daishi visited Yashimaji at the behest of Emperor Saga. He moved the temple from the northern peak to the southern peak, carved the 11-faced, thousand-armed Kannon, and enshrined it within the temple. Yashimaji flourished as a sacred place for mountain Buddhism. When we arrive, there’s a devotee chanting sutras on the steps of the Hondo.

Almost all the Buddhist temples we visit in Kagawa have a Shinto shrine close by or incorporated into the temple. With its vermilion torii gates and animist sculptures, Yashimaji is no exception. One of these images is a tanuki, a Japanese raccoon dog that is a mainstay of Japanese folklore. It’s believed to be able to change its shape and play tricks on the wicked and unsuspecting.

We spend the night at a hotel in a national park, high up in the mountains. Our room looks out onto the Seto Inland Sea and as the sun sets, we sit and watch the passage of ships and the play of the wind. The serenity is intoxicating.

Day 43: 23 km/Temples 85-87

Last night, the hotel manager asked if Japanese food was available in Australia. This led to a conversation about Australian cuisine more generally. When we explained that migrants had brought their different food cultures with them, she responded: So, you have a lot of foreigners in Australia. We were a little taken aback as we don’t think of all those Australians who come from afar (including Anna’s mother) as foreigners. Japan is changing as it forms a new vision of who belongs to the nation but obviously, there are still significant barriers to immigrants becoming ‘Japanese’.

We drop to sea level before climbing again, this time to Yakuriji (Temple 85). On the way, we pass Sainokawara, the Children’s Limbo, believed to be the boundary between the human and the sacred world. Before we enter the temple grounds we pause to take in the view over the Sanuki Plain. It’s dotted with mountains, including a mysterious peak that resembles a sword pushed up from the ground. The Welcoming Daishi is seated on a dais high above the ground. People stand before it; praying for academic achievement, marriage, and business prosperity.

The steep and wild Shikoku Mountain Range runs east/west through the island’s centre and is home to two of Japan’s most famous mountains; Mount Kenzan and Mount Ichizuchisan. Their peaks are holy ground for practitioners of Shugendō, an indigenous form of mountain worship and asceticism. We walk up and down mountain paths on this cool, sunny morning to arrive at Shidoji (Temple 86). It’s on the coast facing Shido Bay and is one of Shikoku’s oldest temples. Created in the 15th century, its garden was damaged by an earthquake and left in ruins. Mirei Shigemori, a Japanese landscape architect, resurrected the ancient garden in 1962. He added a zen-style dry landscape garden that expresses the landscape of the Seto Inland Sea using seven dark stones, moss-covered rocks, and ripples of raked white sand.

Tranquil Nagaoji (Temple 87) is the penultimate temple of the Shikoku Pilgrimage. It faces Nankai Road, one of Japan’s ancient thoroughfares. Kōbō Daishi visited here and prayed for the first seven nights of the year for national security, abundant harvests of the five grains, and the temple’s prosperity. The prayer continues to this day.

Between Nagaoji and Okuboji (Temple 88) there’s a henro museum that issues certificates of completion to walking henros. We’re greeted with a smile, certified as Ambassadors of the Shikoku Pilgrimage and presented with a pair of lucky chopsticks.

Neil is staying at the same guest house as us this evening and we chat over instant ramen. He says he came across the Shikoku Pilgrimage while travelling in Japan 25 years ago. He resolved to walk it one day, not expecting such a long time to elapse before he set out. (His life has been busy in the intervening years with a career, a partner, two children, etc.)

Day 44: 37 km/Temple 88

A miscalculation in Michael’s planning means we have a long day’s walk ahead. We’re on the road before dawn. The sky lightens. The flattened rice straw is white with frost. Steam rises from pools of water. Monkeys scamper in and out of the forest.

Five kilometres from Okuboji (Temple 88) we stop at a rest area. A woman gives us what we imagine is our last osettai; two warm matcha buns filled with red bean paste, a regional speciality.

A steep mountain peak rises from behind the temple. An eternal flame: a memorial to the atomic bombings. Lest we forget. A large entrance gateway, lichen-covered stone statues, and 88 small shrines. On this crisp sunny Sunday, the temple grounds are full of picnicking families, delighting in the autumn colours that are vivid, almost fluorescent at this altitude.

Okuboji is the culmination of an epic journey. Ray, our brother-in-law, has been in our thoughts. He would have wanted us to return to Japan and finish the Shikoku Pilgrimage; we’re pleased to have done so. A turmeric-robed monk draws the last temple seal in our books to mark the end of our 1,200-kilometre walk. We bow and leave the temple precinct to the frolicking children.

Descending the mountain, we walk through a semi-abandoned valley for many kilometres until we reach the coast. The day is long but despite the lack of available food on this deserted Sunday, we have strength in our step.

Day 45: 18 km/Temple 1

The morning sparkles. We walk out along the seawall before heading into the mountains on an old way, across the Oosaka Pass. Today is about closing the circle by walking back to Ryozenji (Temple 1) where we started the journey all those months ago. We recognise the landscapes as quintessentially Japanese. Dishevelled by earthquakes and abandonment. The past slow to concede ground to the present: the future its own whirlwind.

One last mountain pass before descending to the outskirts of Tokushima where we linger over a can of hot coffee from a vending machine. We walk through Konsenji (Temple 3) and on to Ryōzenji. In 815, when Kōbō Daishi was walking around Shikoku, he conducted prayers and austerities here, hoping to establish a place where people could free themselves from the 88 worldly desires. He enshrined the little Buddha effigy he carried with him, indicating his intention to make Ryōzenji the first of an 88-temple pilgrimage, every temple visit helping henros to purify themselves.

The return to Ryozenji is a little surreal. Groups of henros in clean white outfits are setting out on the first day of their pilgrimage. The monk in the temple office is perfunctory. He stamps our books and because we’re slow with the fee, holds on to them until we hand him the money. We wander the temple precinct, reacquainting ourselves with a place that is both familiar and strange. Then all that is left is to walk to Bando station and catch a train to Tokushima.

At the Tokushima Visitors Welcome Centre, we‘re presented with a certificate of completion and applauded for our efforts. We have dinner and a celebratory drink with Neil. He says his long pilgrimage has changed him, although he doesn’t know what path this will take him down when he returns home. As for us, we stopped trying to make something of the search for Nirvana as we moved through Kagawa; the string of calm, contemplative days and finishing the 1,200-kilometre pilgrimage is enough of a blessing.

Epilogue

The day after we finished the Shikoku Pilgrimage we crossed the Seto Inland Sea and journeyed through the mountains to the secluded temple town of Koyasan, one of Japan’s most sacred places.

After attaining enlightenment on Shikoku, Kōbō Daishi established the headquarters of Shingon Buddhism in Koyasan in the 9th century. He remains here in eternal meditation, waiting for the arrival of the Buddha of the Future. Ancient cedar trees stand along the approach to his mausoleum and twice a day Buddhist monks carry food prepared for him up through the trees to the hall of 10,000 lanterns. The offering is evidence that Kōbō Daishi still exists in eternal prayer.

Mystical, mysterious, beautiful Koyasan is the ultimate end point of our Shikoku Pilgrimage. A temple official inscribes our visitor books and takes time to explain the meaning of the Sanskrit characters she has so beautifully drawn. We thank her, bow, and take our leave.

A hand moves and the fire’s whirling takes different shapes. Triangles, squares: all things change when we do. The first word, ‘Ah’ blossomed into all others. Each of them is true. Kōbō-Daishi, founder of Shingon Buddhism, 774-835 СЕ

—————-

This is our fourth and final story on walking the Shikoku Pilgrimage. The first stage through Tokushima Prefecture is the awakening of the spirit. Kochi Prefecture, the second, is the stage of austerity and discipline, while the third stage, Ehime, represents the search for enlightenment.

Thank you for sharing and inspiring. We’re walking the Shikoku-88 in April and May and intend to camp at least 10 nights. From your recent experience and observations – is camping as ill advised as many are saying?

Cheers, Casper (South Africa )

Hi Casper, There are official campgrounds and we understand the number of places where camping might be allowed outside of official campgrounds is reducing as the number of Henros increases. The guidebook and HenroHelper app will give guidance on where camping may be allowed however, unless it is very clear that camping is allowed, you need to ask permission from locals.

This is a good summary of the situation https://www.facebook.com/groups/999427673485587/permalink/6737894622972168/

Ganbatte kudasai

Thank you, we have no intention to camp without proper permission, it’s just difficult to get a good idea whether there are enough official, bona fide camping options on route.

We met only briefly in the guesthouse in Naoshima. I was on my way back to Osaka for my flight back home. The two of you were about to set off the pilgrimage. Been follwing your journey a bit in Instagram. Great you returned after your brother-in-law’s passing and completed your journey. I am thinking of visiting Shikoku this year for a month, but just to explore. I might do some walking, but not as a henro yet. That’s for the (near) future when my general fitness level is up enough for a walk like this.

Paul

Hi Paul We well remember meeting you and have been thrilled when your fabulous Geisha photos appear on our Instagram feed. We hope you get to Shikoku and enjoy exploring it. Let us know if can assist with any information.

Cheers

Michael & Anna

What a wonderful adventure and achievement. Thanks for sharing it with us. Mel

Hi Mel, We’re very pleased that you enjoyed our story (as we did reading of your amazing walk in Nepal)

Michael & Anna

I have enjoyed reading about your pilgrimage. My husband and I were about a week ahead of you and often saw your posts on Facebook. We wrote about our journey on our blog seekinghorizons.com. We have several pictures of the same people that we met. We also concluded our pilgrimage by visiting Koyasan. It was an amazing experience for us as well. Before we went to Japan last year we spent several months hiking in Australia, mostly in Tasmania. Australia is an amazing country! thanks for sharing your story.

Hi Donna

We’re pleased that you enjoyed our story. Reading your account of the pilgrimage was a delight, seeing familiar faces and places brought back so many good memories for us. You had excellent weather for your Overland Track walk, it’s one of our (and many Australians) favorites.

Here’s to many more adventures…

Ganbatte kudasai

Your pilgrimage is like life – sometimes beautiful, sometimes sad, often weird, but always wonderful!

Thank you for reminding me.

Thanks so much for your beautiful words – always appreciated.